Surgical Colouring

Mr Robert Wheeler FRCS (Eng) Southampton

My father was a commercial artist, but I lacked his talent. Instead, from an early age, I sought a surgical career, amongst others. Although I still struggle to draw accurately in three dimensions, I have an enduring, undiminished passion for colour. However I could not find in daily life any real application for that interest. I am therefore eternally grateful to an unhurried anaesthetist with whom I worked with 35 years ago in Southampton General Hospital. It occurred to me that it might be possible to record the surgical anatomy of my patients in watercolours before the patient left the operating theatre, and my colouring career began.

My father was a commercial artist, but I lacked his talent. Instead, from an early age, I sought a surgical career, amongst others. Although I still struggle to draw accurately in three dimensions, I have an enduring, undiminished passion for colour. However I could not find in daily life any real application for that interest. I am therefore eternally grateful to an unhurried anaesthetist with whom I worked with 35 years ago in Southampton General Hospital. It occurred to me that it might be possible to record the surgical anatomy of my patients in watercolours before the patient left the operating theatre, and my colouring career began.

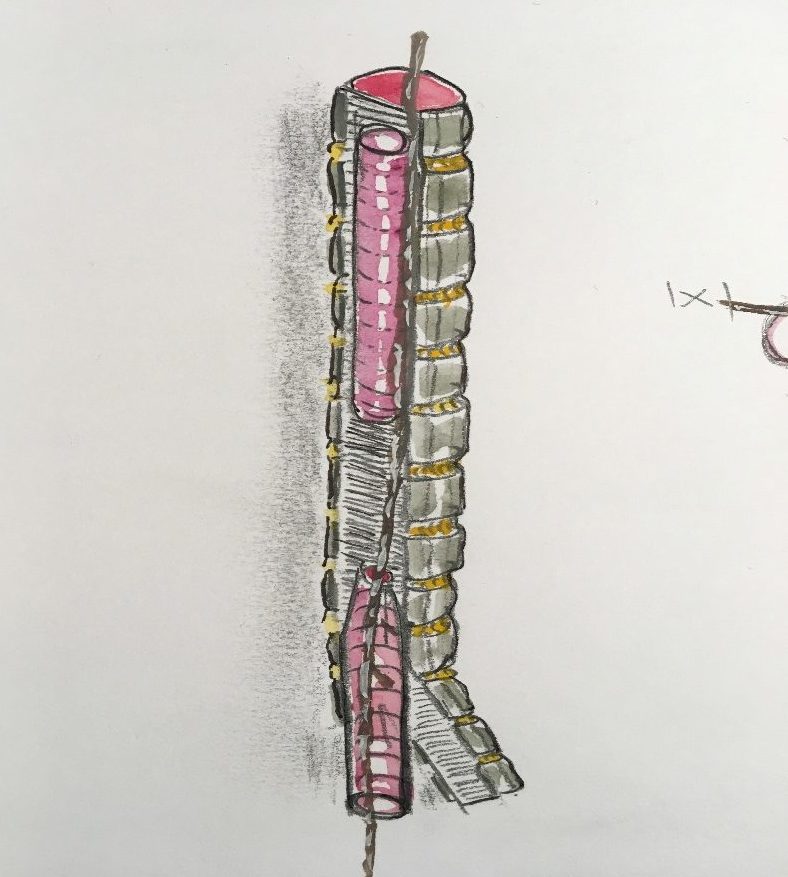

From that point, I have produced perhaps 500 watercolours filed in the surgical notes, whilst that anaesthetist has long since departed. The bulk of these derive from emergency operating and tumour resection (my principle and enduring surgical interest, but notable anatomy or pathology encountered on an elective surgical day-case list may also pique my interest and prompts my colouring (FIG. 1). Few of these pictures have taken me more than 15 minutes, so it is possible to finish the watercolour without prolonging the operating session. Currently, in the name of progress, our paper patient notes are being ‘phased out’ (and ultimately consigned to the incinerator as it happens) as we learn to enjoy the benefits of an entirely electronic record system. Perforce, I now scan the watercolour, storing it as an image file in the patient’s record.

Uncharacteristically dumbfounded by this colouring eminent colleagues wonder why I bother. What follows is my way of rationalising this activity.

“Painting as a pastime”. When in doubt, quote Winston Spencer Churchill…This the title of his glorious book on the subject published in 1948. His views chime with mine; “I prefer landscapes. A tree doesn’t complain that I haven’t done it justice”.

I am under no illusions that this is ‘art’, hence my title. But I honestly don’t care, being constantly fascinated by the spidery march of strong colour through clear water, still enchanted as primary colours meet then transmutate. Tubes of paint particularly appeal to me. Nonetheless, I must seek better justification.

Preliminaries

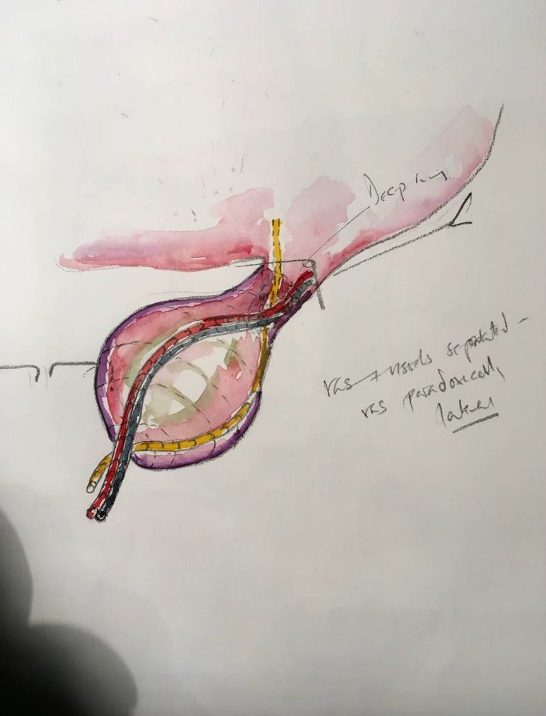

The roughest sketch in outpatients or awaiting emergency surgery helps disclosure when seeking consent. To see how the vas and vessels relates to the peritoneal tube that contains herniated viscus alerts the parents to the reality of the risk to those structures during herniotomy, whilst explaining why spontaneous resolution is unlikely.

Preparation

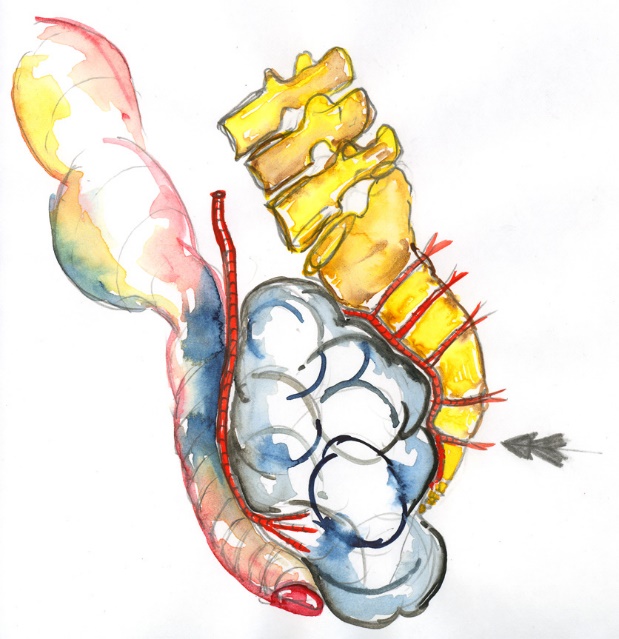

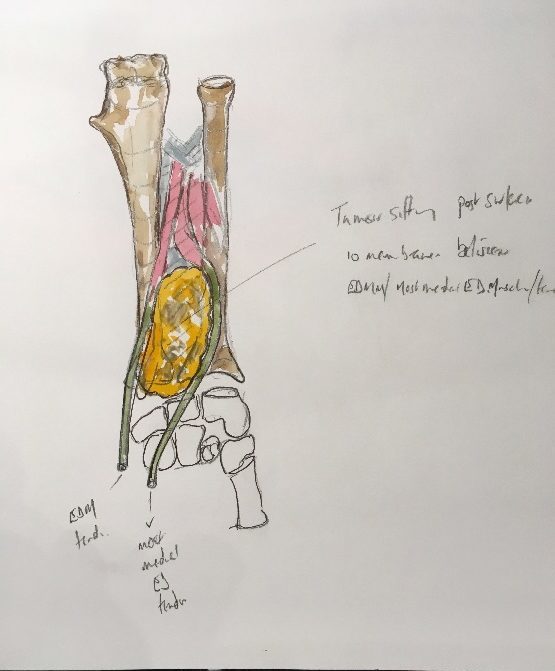

In common with many other surgeons, I spend many hours absorbing the imaging prior to tumour excision. This allows a detailed mental plan to crystallise of what will be encountered and how to deal with the surgical challenge or what to do if, or perhaps, when the best-laid plans go wrong. I suppose most of us do that. Over the last 10-15 years I have increasingly drawn outline sketches during this planning stage (although still no colouring prior to closing the skin, since that’s presumptuous and tempts disaster). By committing on paper to the position of the tumour relative to the vasculature and adjacent structures, the operative plan coalesces; often exposing weakness or error which can then be resolved by changing the strategy. I would strongly recommend this approach; all paediatric surgeons are confronted with operations they have never done before, and this is a way of assuaging both uncertainty and fear. In a different ‘preparation’; that for talks, I have occasionally coloured an image to illustrate a specific point (Figure 3).

Postoperative

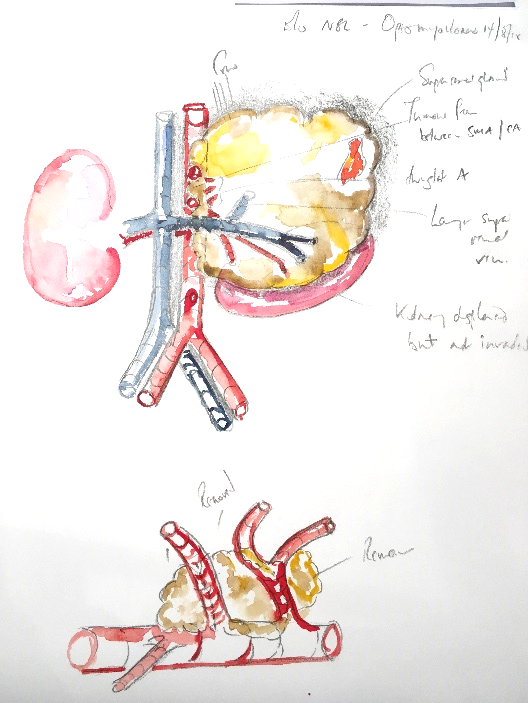

Parents are usually pleased to see a picture hinting at what was encountered intraoperatively. At best, they may have seen their baby’s red and swollen belly or a black and white image on a screen by means of explanation for surgery. But they will likely never have seen inside a human, and can have little idea what the surgeon actually saw. The watercolour helps them a little, often prompting questions. (Fig. 4) Since they may now see the context of the adjacent structures, thus seeking to know the degree that the disease has influenced the anatomy at its perimeter. Some parents wish to accumulate a journal of their child’s voyage through their disease, and welcome a tangible record of what went on. Either way, nowadays most parents record the watercolour on their smart phones. Equally, most clinical staff charged with postoperative care have had no sight of this child’s pathology. They may also lack experience in managing the first few days of the surgical aftermath of excisional surgery. For both of these reasons, tempting the staff to view a watercolour (if only then wryly to smile) may help to engage them with further their patient.

Outpatients

During outpatient follow up, there is no doubt I would be lost without the picture. We all perform our index operations near-countless times; in my case, I honestly cannot distinguish the memory of the excision of one Wilms’ or neuroblastoma or germ cell tumour from another once a few months have elapsed. I do make detailed written records, but the watercolour recalls details and difficulties in an instant…hence the importance of ensuring the image enters the electronic notes, allowing rapid orientation in clinic (Fig.5).

Providing materials

Countless operative diagrams appear in print and on line, but it seems commonplace to encounter a crucial moment during surgery when you really need a diagram that apparently has yet to be drawn….or where the conventional image misses the point. Some of my colourings have been prompted by these apparent lacunae, including the entry of the distal oesophageal fistula into the posterior, rather than lateral aspect of the trachea. (Fig. 6)

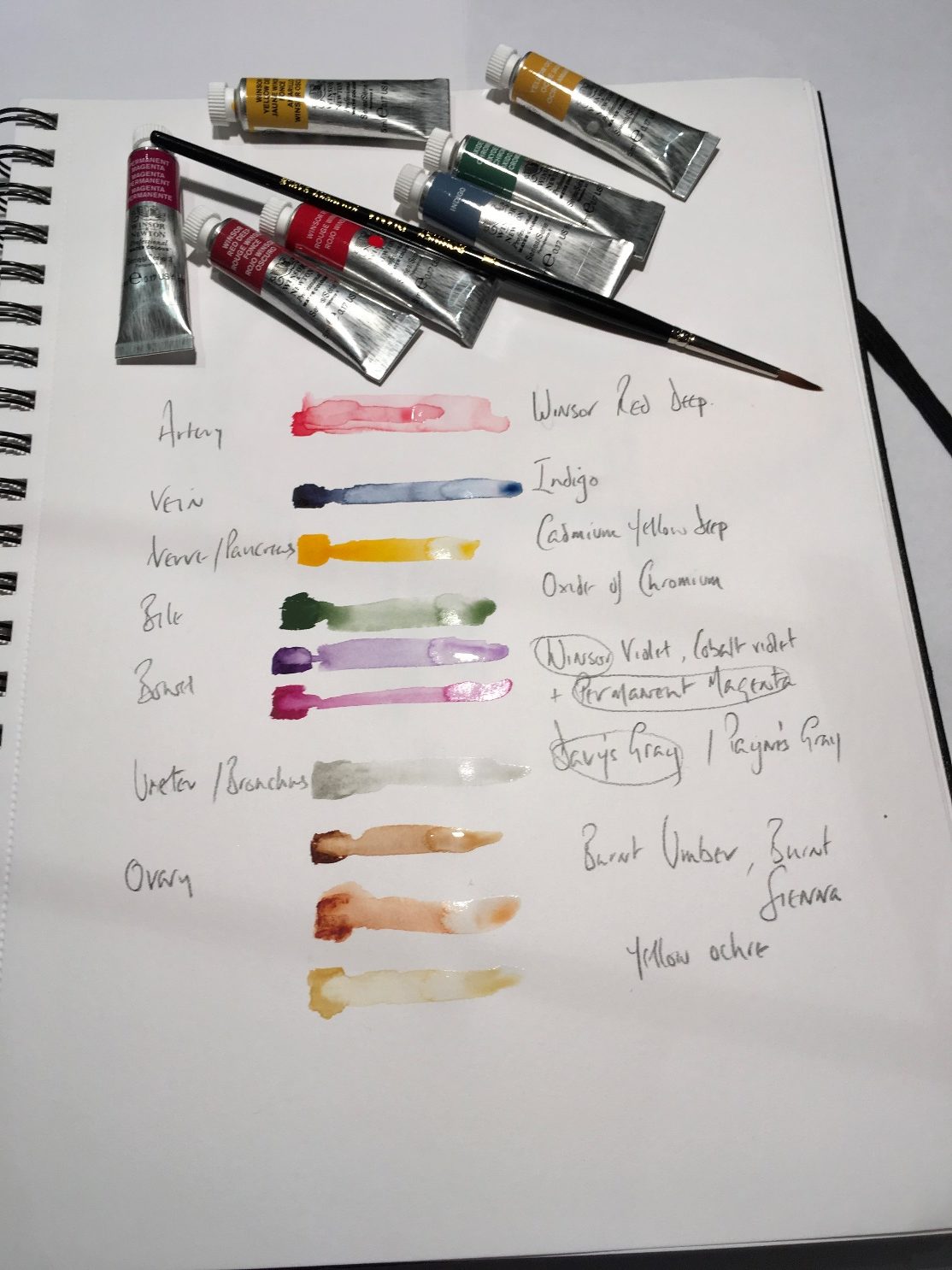

Colour Chart

If you are tempted…here are some colour suggestions (Fig. 7)

Surgical colouring may still seem to you a hollow exercise, conferring no benefit. But if unconvinced, bear in mind WSC: ‘Never trust a man who has not a single redeeming vice.’

Robert Wheeler, BAPS member, Children’s Surgeon, Academic Lawyer.

http://www.uhs.nhs.uk/HealthProfessionals/Clinical-law-updates/Clinicallawupdates.aspx

University Hospital of Southampton, March 2019.

[Edited Mark Davenport 9th April 2019]